- TOPICS

- Spreading humanitarian competition and fostering global-minded citizens essential for achieving SDGs

Professor Popovski with his students

2019/08/08

Spreading humanitarian competition and fostering global-minded citizens essential for achieving SDGs

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development adopted by all United Nations member states in 2015 lays out a road map to create a better future for people and the planet. At the heart of this agenda are 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs), which include eradicating extreme poverty, ensuring quality education and gender equality and combatting global warming. Governments, companies, educational institutions and other entities across the globe are striving to achieve these goals, but accomplishing them before the target year of 2030 remains a challenge.

Professor Vesselin Popovski of Soka University’s Graduate School of International Peace Studies weaves these SDGs into his study of sustainability and peace. We asked Popovski, an expert on international relations, peace and security, human rights and international law, about the difficulties hindering the implementation of Climate Action (Goal 13), as well as issues related to Quality Education (Goal 4). The following article is based on that interview.

Key points

・The United States re-committing to the Paris Agreement on climate change is essential for stopping global warming

・Short-sightedness often pushes the climate agenda to the sidelines

・Humanitarian competition is crucial for addressing climate change and other SDGs

・Education is key to promoting humanitarian competition

Soka University Professor Vesselin Popovski says it is vital that the United States re-commits to the Paris Agreement on fighting climate change if the world wants to achieve the long-term goal of keeping the increase in global average temperature to well below 2 C above pre-industrial levels.

The Paris Agreement, which was adopted in December 2015 and is scheduled to enter into force in 2020, faces a bumpy road. U.S. President Donald Trump announced in 2017 his intention to withdraw his country from the agreement, saying it “punishes” the United States while imposing “no meaningful obligations” on China and India, the largest and third-largest emitters, respectively, of carbon dioxide (as of 2017). Trump is expected to start withdrawal procedures in November and formally pull the United States from the accord as early as 2020.

Popovski, who edited “The Implementation of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change” (Routledge, 2018), said Trump’s rejection of Barack Obama’s ambitious anti-global warming policies will face a pushback.

“I am rather optimistic because the United States is a democratic nation,” Popovski said of the chance that the United States, the second-largest CO2 emitter, might return to the Paris Agreement. Indeed, some U.S. politicians and businesses have recently spoken out about Trump’s plan. Furthermore, in May 2019, the U.S. House of Representatives passed legislation to block Trump from withdrawing from the deal. The following month, a group of major automakers sent Trump a letter objecting to his plan to weaken vehicle emission standards, a move they say will jeopardize their profits and produce “untenable” instability in the automobile industry.

Popovski said the international community’s lack of urgency in tackling global warming is troubling. “The problem is that environmental change and climate change are not always in the front of people’s minds because they are long-term trends,” Popovski said. “They are serious issues, but when people wake up in the morning and see the sun and beautiful trees and greenery outside, they don’t immediately feel threatened by climate change. So they don’t realize that if nothing is done today, it will be too late to deal with these problems 20 years from now.”

This trend is evident also in the political arena. Even in Europe, which has long championed environmental protection, the green agenda has slipped down the list of priorities following the rise of populists and nationalists who want to chip away at the European Union’s power and introduce anti-immigration policies, Popovski said.

However, Popovski found a ray of hope in gains made by the Greens in the European Parliament elections in May 2019 and says it is essential to create a multinational alliance to push the green agenda to the center stage.

Humanitarian competition key to achieving SDGs

So how can we promote the green agenda?

According to Popovski, the concept of humanitarian competition – competition in the mutual striving for excellence – will be instrumental in encouraging the world to act responsibly and fight climate change. “Climate action is the best example of how we can use this concept,” Popovski said. “We can’t think selfishly about only ourselves because the air, water, and oceans are the same for everybody. All nations should realize they must act together to save the world.”

The humanitarian competition was first advocated more than 100 years ago by Tsunesaburo Makiguchi (1871-1944), an insightful geographer, educational theorist, and religious reformer, whose opposition to Japan’s militarism and nationalism resulted in his imprisonment and death during World War II. Makiguchi called for exercising the competitive power of people in conformity with the principle of humanitarianism, rather than in the military, political and economic domains.

In fact, Popovski assumed his current position at Soka University because he wanted to teach students how important humanitarian competition is for ensuring sustainability and peace, the theme of his research at his previous job at the United Nations University in Tokyo. Makiguchi is the founder of Soka Gakkai, Japan’s largest lay Buddhist organization. Soka Gakkai Honorary President Daisaku Ikeda founded Soka University in 1971.

Popovski is a member of the Soka University Peace Research Institute, which was established in 1976 with a commitment to realizing a peaceful society and improving human welfare through research on peace.

“We connect the two concepts of sustainability and peace, which are parallel objectives of humanity,” said Popovski. “We need to think about our children and grandchildren. We must take action today so the generations to come will not be negatively affected. There are limits to resources such as forests, water, and land. We must act responsibly for the coming generations. That is important for sustainability.”

Quality education vital for spreading the concept of humanitarian competition

Popovski said the concept of humanitarian competition can be spread more broadly through quality education. If students are taught about the idea of harnessing humanitarian competition to attain sustainability and peace, they will advocate this concept after entering adult society. “They will not just talk about it. They’ll also act responsibly to achieve the SDGs,” he said. “It will be a long road, but if we do this work every day with the right methodology, we will achieve that goal. I think my role is to educate the next generation of global-minded citizens about sustainability and peace.”

In particular, Popovski underscored the importance of teaching students about peace, which encompasses the concepts of development, human rights, good governance, and human security, to name but a few. “That’s why we put SDGs in our core research,” Popovski explained.

Soka University educates students to become global-minded citizens who can think analytically and critically. The university has been selected for the government’s Top Global University Project to lead the globalization of Japanese society. It has accepted 550 international students from 50 countries and regions and offers various study-overseas programs and internship and volunteer programs in foreign countries.

“It is good being a model university” showing other universities in Japan how to nurture students with a global perspective, Popovski said. “I am very happy that Soka University excels in teaching students how to become good global citizens.”

Vesselin Popovski

Popovski is researching the themes of global approaches to peace and the responsibility to protect, and the development of international law. The Bulgarian-born professor was educated at Moscow Institute of International Affairs, London School of Economics and King’s College London. He taught and/or conducted research at the University of Exeter (Britain), United Nations University (Japan) and Jindal Global University (India) before taking up a professorship at Soka University.

Professor Vesselin Popovski of Soka University’s Graduate School of International Peace Studies weaves these SDGs into his study of sustainability and peace. We asked Popovski, an expert on international relations, peace and security, human rights and international law, about the difficulties hindering the implementation of Climate Action (Goal 13), as well as issues related to Quality Education (Goal 4). The following article is based on that interview.

Key points

・The United States re-committing to the Paris Agreement on climate change is essential for stopping global warming

・Short-sightedness often pushes the climate agenda to the sidelines

・Humanitarian competition is crucial for addressing climate change and other SDGs

・Education is key to promoting humanitarian competition

Soka University Professor Vesselin Popovski says it is vital that the United States re-commits to the Paris Agreement on fighting climate change if the world wants to achieve the long-term goal of keeping the increase in global average temperature to well below 2 C above pre-industrial levels.

The Paris Agreement, which was adopted in December 2015 and is scheduled to enter into force in 2020, faces a bumpy road. U.S. President Donald Trump announced in 2017 his intention to withdraw his country from the agreement, saying it “punishes” the United States while imposing “no meaningful obligations” on China and India, the largest and third-largest emitters, respectively, of carbon dioxide (as of 2017). Trump is expected to start withdrawal procedures in November and formally pull the United States from the accord as early as 2020.

Popovski, who edited “The Implementation of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change” (Routledge, 2018), said Trump’s rejection of Barack Obama’s ambitious anti-global warming policies will face a pushback.

“I am rather optimistic because the United States is a democratic nation,” Popovski said of the chance that the United States, the second-largest CO2 emitter, might return to the Paris Agreement. Indeed, some U.S. politicians and businesses have recently spoken out about Trump’s plan. Furthermore, in May 2019, the U.S. House of Representatives passed legislation to block Trump from withdrawing from the deal. The following month, a group of major automakers sent Trump a letter objecting to his plan to weaken vehicle emission standards, a move they say will jeopardize their profits and produce “untenable” instability in the automobile industry.

Popovski said the international community’s lack of urgency in tackling global warming is troubling. “The problem is that environmental change and climate change are not always in the front of people’s minds because they are long-term trends,” Popovski said. “They are serious issues, but when people wake up in the morning and see the sun and beautiful trees and greenery outside, they don’t immediately feel threatened by climate change. So they don’t realize that if nothing is done today, it will be too late to deal with these problems 20 years from now.”

This trend is evident also in the political arena. Even in Europe, which has long championed environmental protection, the green agenda has slipped down the list of priorities following the rise of populists and nationalists who want to chip away at the European Union’s power and introduce anti-immigration policies, Popovski said.

However, Popovski found a ray of hope in gains made by the Greens in the European Parliament elections in May 2019 and says it is essential to create a multinational alliance to push the green agenda to the center stage.

Humanitarian competition key to achieving SDGs

So how can we promote the green agenda?

According to Popovski, the concept of humanitarian competition – competition in the mutual striving for excellence – will be instrumental in encouraging the world to act responsibly and fight climate change. “Climate action is the best example of how we can use this concept,” Popovski said. “We can’t think selfishly about only ourselves because the air, water, and oceans are the same for everybody. All nations should realize they must act together to save the world.”

The humanitarian competition was first advocated more than 100 years ago by Tsunesaburo Makiguchi (1871-1944), an insightful geographer, educational theorist, and religious reformer, whose opposition to Japan’s militarism and nationalism resulted in his imprisonment and death during World War II. Makiguchi called for exercising the competitive power of people in conformity with the principle of humanitarianism, rather than in the military, political and economic domains.

In fact, Popovski assumed his current position at Soka University because he wanted to teach students how important humanitarian competition is for ensuring sustainability and peace, the theme of his research at his previous job at the United Nations University in Tokyo. Makiguchi is the founder of Soka Gakkai, Japan’s largest lay Buddhist organization. Soka Gakkai Honorary President Daisaku Ikeda founded Soka University in 1971.

Popovski is a member of the Soka University Peace Research Institute, which was established in 1976 with a commitment to realizing a peaceful society and improving human welfare through research on peace.

“We connect the two concepts of sustainability and peace, which are parallel objectives of humanity,” said Popovski. “We need to think about our children and grandchildren. We must take action today so the generations to come will not be negatively affected. There are limits to resources such as forests, water, and land. We must act responsibly for the coming generations. That is important for sustainability.”

Quality education vital for spreading the concept of humanitarian competition

Popovski said the concept of humanitarian competition can be spread more broadly through quality education. If students are taught about the idea of harnessing humanitarian competition to attain sustainability and peace, they will advocate this concept after entering adult society. “They will not just talk about it. They’ll also act responsibly to achieve the SDGs,” he said. “It will be a long road, but if we do this work every day with the right methodology, we will achieve that goal. I think my role is to educate the next generation of global-minded citizens about sustainability and peace.”

In particular, Popovski underscored the importance of teaching students about peace, which encompasses the concepts of development, human rights, good governance, and human security, to name but a few. “That’s why we put SDGs in our core research,” Popovski explained.

Soka University educates students to become global-minded citizens who can think analytically and critically. The university has been selected for the government’s Top Global University Project to lead the globalization of Japanese society. It has accepted 550 international students from 50 countries and regions and offers various study-overseas programs and internship and volunteer programs in foreign countries.

“It is good being a model university” showing other universities in Japan how to nurture students with a global perspective, Popovski said. “I am very happy that Soka University excels in teaching students how to become good global citizens.”

Vesselin Popovski

Popovski is researching the themes of global approaches to peace and the responsibility to protect, and the development of international law. The Bulgarian-born professor was educated at Moscow Institute of International Affairs, London School of Economics and King’s College London. He taught and/or conducted research at the University of Exeter (Britain), United Nations University (Japan) and Jindal Global University (India) before taking up a professorship at Soka University.

Professor Popovski giving a presentation

Professor Popovski

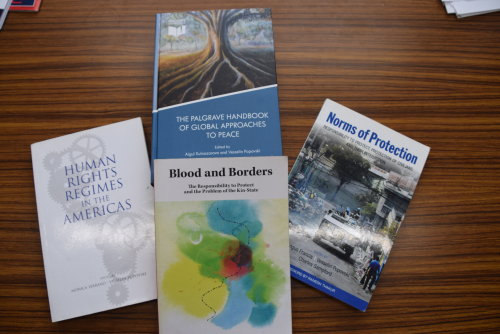

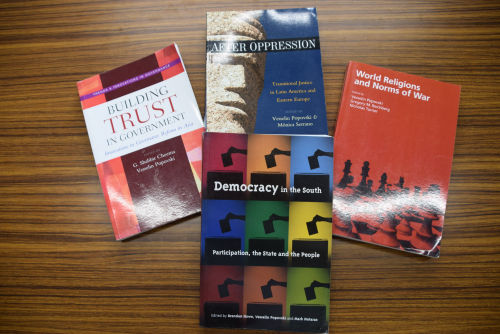

Books Published by Professor Popovski

Books Published by Professor Popovski

ページ公開日:2019/08/08