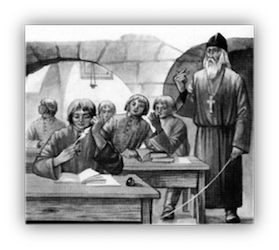

Lomonosov's life and Russian chronology

The life of Mikhail Lomonosov

Early life

Mikhail Lomonosov was born on November 19, 1711. The early 18th century was a time of great change in Russia, when Peter the Great was pushing through almost universal reforms in society.

It was a time of great change: Russia expanded, natural resources were developed, a new capital was built, a fleet was founded, the calendar was reformed (the medieval cosmological calendar was replaced by the Gregorian calendar), the first newspapers and museums were opened, educational institutions for the general public were established, and even the Academy of Sciences was founded, which left a significant mark on Russian history.

It was a time of great change: Russia expanded, natural resources were developed, a new capital was built, a fleet was founded, the calendar was reformed (the medieval cosmological calendar was replaced by the Gregorian calendar), the first newspapers and museums were opened, educational institutions for the general public were established, and even the Academy of Sciences was founded, which left a significant mark on Russian history.

Peter I

The educational and academic systems were then developed as special national institutions. This trend coincides with the progress of European history as it entered the Age of Enlightenment.

Lomonosov was born in the northern region of Arkhangelsk Oblast, on an island on the Northern Dvina River, which flows into the White Sea. In winter, the river froze over and people could walk along the ice to the nearby town of Kholmogory.

The river was an important route for merchants, who carried their goods along it, and foreign trade passed through Kholmogory, making it a key crossing point with Western Europe during the reigns of Ivan the Terrible and Peter the Great.

The river was an important route for merchants, who carried their goods along it, and foreign trade passed through Kholmogory, making it a key crossing point with Western Europe during the reigns of Ivan the Terrible and Peter the Great.

Lomonosov's father, Vasily, made his fortune from fishing and farming. He built the first local galliot (a two-masted sailing ship), which he named Chaika.

Like other peasant children, young Mikhail helped his parents with their work. They grazed livestock, cultivated the fields, and at the age of 10, he began going out to sea with his father to fish. Sea fishing was a major source of income for local farmers, so they spent almost half the year at sea, going out in the spring and returning in the fall. Through fishing, Mikhail learned about the beauty and danger of nature, and grew up with many experiences, including meeting foreigners who whaled in the White Sea and foreign merchants.

Soon Mikhail showed an extraordinary love of learning.

All locals are trained to do things like raise a flag, use a compass, learn about the habits of the sea and its creatures, and observe the unpredictable weather in the north. But Mikhail didn't just learn these tasks; he went deeper, trying to answer his own questions. Why does the wind blow? What force makes a compass needle always point north? Why do fish swim against the current to spawn? Why do the auroras occur? Why do day and night, high tides and low tides alternate? Mikhail wanted to know everything.

All locals are trained to do things like raise a flag, use a compass, learn about the habits of the sea and its creatures, and observe the unpredictable weather in the north. But Mikhail didn't just learn these tasks; he went deeper, trying to answer his own questions. Why does the wind blow? What force makes a compass needle always point north? Why do fish swim against the current to spawn? Why do the auroras occur? Why do day and night, high tides and low tides alternate? Mikhail wanted to know everything.

However, his parents could not understand the intense enthusiasm of their son for learning. Mikhail's mother died of illness when Mikhail was still a child. His father remarried, but her second wife also died soon after, so he married a third time. His stepmother was a nagging woman who would tell his father if Mikhail was reading a book. At that time, most local residents could not read or write, and Lomonosov's father was no exception. At first, his father was favorably disposed towards his son's desire to learn, but he soon became influenced by his stepmother's slander.

Mikhail was able to get out of the house because his neighbor had a book, which was unusual for the time.

He borrowed and read books from the library. There was also an Old Believers' base nearby, and he went there to buy books. However, Mikhail's desire to learn was still not satisfied, and he began to dream of going to Moscow to study.

He borrowed and read books from the library. There was also an Old Believers' base nearby, and he went there to buy books. However, Mikhail's desire to learn was still not satisfied, and he began to dream of going to Moscow to study.

At that time in Russia, not everyone had the opportunity to receive an education, and children could only learn the family business at home. Children who were eager to learn could only go to church and learn how to read and write.

When Mikhail turned 18, his father decided to marry off his son, who was always absorbed in reading. Mikhail avoided marriage by pretending to be ill, but one day he finally made up his mind and left home. He walked more than 1,000 kilometers to Moscow in search of education. After that, he never set foot on his hometown soil again.

Along the way, he met a traveling fish merchant, and in January 1731, Lomonosov arrived in Moscow. At the fish bazaar, he met some fellow countrymen, who let him stay at their homes and helped him get into school. He then began studying at the Slavic Greek and Latin Institute, Russia's oldest educational institution. At the time, anyone who wanted to study there could study, but peasants were excluded, so Lomonosov lied about his origins as the son of a priest and enrolled. Already 20 years old, Lomonosov studied at the same desk as 12-13 year old children. Despite living in poverty, with no money for books or clothes and barely enough to eat, he was absorbed in his studies. He completed the three-year curriculum in one year. A few years later, it was discovered that Lomonosov was not the son of a priest, but a peasant, and they tried to send him to the military or exile him to Siberia, but

In the end, Lomonosov, a hard-working and excellent student, was allowed to stay on at the school, a humiliation he would never forget and would later try to establish an education system that was open to people of all classes.

In the end, Lomonosov, a hard-working and excellent student, was allowed to stay on at the school, a humiliation he would never forget and would later try to establish an education system that was open to people of all classes.

The Slavic, Greek and Latin Institute had many excellent teachers who had returned from abroad, but it was primarily a school for training clergy and translators, and the subjects taught were mostly humanities, such as languages, philosophy and theology, and physics was taught based on the works of Aristotle, so it was clearly outdated.

Academy of Sciences [1]

At that time in Russia, the only place where research in natural sciences such as physics, mathematics, and geography was conducted was the St. Petersburg Academy, founded by Peter the Great in 1724. Renowned foreign scholars invited from all over Europe worked at the Academy. Peter the Great envisioned the Academy not only to conduct research, but also to educate Russian students, and an affiliated university was established for that purpose. At the time, there was no system in Russia that allowed for systematic academic research. The Academy was established with the goal of improving the situation and catching up with Europe. However, the affiliated university was practically closed.

Then, in 1735, twelve outstanding students from the Slavic, Greek and Latin Institute were sent to the Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg. Lomonosov was one of them. The purpose of this assignment was to revitalize the university attached to the academy; up until then, even though there were famous scholars there, there were no students who could understand their lectures. However, the foreign scholars had no desire to contribute to education in Russia, and the goal of revitalizing the university was not achieved.

[1] An academic organization established to promote research in science (including humanities and social sciences). Currently known as the Russian Academy of Sciences, it encompasses all academic research institutions in Russia.

Study in Germany

At that time, one of the Academy's tasks was to investigate Russia's natural resources, and an expedition had been sent to Siberia, but there were no mining experts. It was decided that students who could become experts in mining would be sent to Germany to study, and in 1736

In 1890, Mikhail Lomonosov, Dmitry Vinogradov, and Gustav Leysel were sent to Marburg, Germany, where they were given the opportunity to study the most cutting-edge science of the time under the renowned philosopher Christian Wolff. Lomonosov was absorbed in his studies of physics under Wolff.

In 1890, Mikhail Lomonosov, Dmitry Vinogradov, and Gustav Leysel were sent to Marburg, Germany, where they were given the opportunity to study the most cutting-edge science of the time under the renowned philosopher Christian Wolff. Lomonosov was absorbed in his studies of physics under Wolff.

The Academy of Sciences gave Lomonosov and the other students more than enough scholarships. In an environment completely different to his previous life of poverty, Lomonosov devoted himself to his studies, but he was also not indifferent to leisure, and he would go out drinking with the other students and get into debt. During their two and a half years in Marburg,

The debts that Lomonosov had incurred were paid off by his mentor Wolf, and after that, the scholarships from the Academy of Sciences were reduced to one third and sent to professors rather than to students. When he went to Freiberg to study mining, his supervisor was Johann Henkel. Taking advantage of the fact that Henkel was not obliged to inform students of the details of their scholarship expenditures, he only handed out very limited amounts of scholarship money, which often led to conflicts between the two. Lomonosov was also dissatisfied with Henkel's teaching, and wrote the following to I. Schumacher, who was then Secretary of the Academy of Sciences:

The debts that Lomonosov had incurred were paid off by his mentor Wolf, and after that, the scholarships from the Academy of Sciences were reduced to one third and sent to professors rather than to students. When he went to Freiberg to study mining, his supervisor was Johann Henkel. Taking advantage of the fact that Henkel was not obliged to inform students of the details of their scholarship expenditures, he only handed out very limited amounts of scholarship money, which often led to conflicts between the two. Lomonosov was also dissatisfied with Henkel's teaching, and wrote the following to I. Schumacher, who was then Secretary of the Academy of Sciences:

"As for chemistry lectures, he (Henkel) spent four months on a lecture on salts that could have been completed in a month, and heavier metals, semimetals, earth elements, stones, sulfur, etc.

There was no time left to study the important subjects. Most of the experiments also failed due to the incompetence of the teachers."

There was no time left to study the important subjects. Most of the experiments also failed due to the incompetence of the teachers."

In the letter, Lomonosov wrote that he had gone to Henkel to complain about his plight, but to no avail, so he left Freiberg. In 1740, he left for Russia. Financially struggling, Lomonosov made money on his journey by weighing things in the market using a scale he had brought as a laboratory tool. However, things did not go as planned due to the absence of the Russian envoy in Germany, whom he had hoped to rely on for the formalities of returning home, so he returned to Marburg.

There, he found his wife, Elizaveta, who was his landlord and to whom he was engaged to be married. They were married that year in 1740[1] and had a daughter. However, Lomonosov told his wife to wait until he was settled in Russia, and left for his homeland.

There, he found his wife, Elizaveta, who was his landlord and to whom he was engaged to be married. They were married that year in 1740[1] and had a daughter. However, Lomonosov told his wife to wait until he was settled in Russia, and left for his homeland.

While searching for a way to return home, Lomonosov wandered around Germany, where he was captured by the Prussian army, tricked into drinking, and forced into military service in the Prussian army. At 2 meters 3 centimeters tall and well-built, Lomonosov was the perfect fit for a soldier.

[1] The wedding took place in a Protestant church in Marburg, but Lomonosov was a Russian Orthodox Christian, a fact that could have raised problems in Russia.

Returning to Japan and battling at the academy

Lomonosov returned to the Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg, where all the professors were German and the language used within the academy was German. This was the result of Peter the Great's policy of inviting many foreign scholars to Russia in order to promote learning in the country. One of the aims of this was to foster Russian scholars, but in reality it was a failure to foster human resources.

The project had not been completed.

The project had not been completed.

Translation was essential to disseminating cutting-edge science from the West to Russia. Lomonosov was also fluent in Greek, Latin, German, French, and Italian, and worked energetically on translation. Academic terms such as "experiment," "motion," "phenomenon," and "particle" did not exist in Russian until then, and Lomonosov translated them to establish Russian terminology. He translated many documents, but he became especially famous for his Russian translation of Christian Wolff's physics textbook. Lomonosov dedicated the textbook to Mikhail Vorontsov, who had great influence in Russian politics at the time, and thus gained his powerful backing.

Lomonosov first gained fame not as a scholar, but as a poet. While he was still studying in Germany, upon hearing the news of Russia's victory in the Russo-Turkish War (1735-1739), he wrote "Poem on the Capture of the Fortress of Khochin" and sent it to Russia, causing a sensation. His poems are characterized by a powerful and majestic sound, and he was not satisfied with existing poetic style, so it can be said that he revolutionized the Russian poetic world with his own works and "Letters on Russian Poetic Style."

Empress Elizabeth also liked Lomonosov's poems, and they were used as a national holiday marker.

He wrote many poems on this theme and received reward for it. One of the reasons why Lomonosov was recognized at court for his poetry and was later able to establish M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University was the presence of Empress Elizabeth's favorite, Ivan Shuvalov (1727-1797). Shuvalov was the only high-ranking official who could report directly to the Empress, and introduced Lomonosov's poems to her. Also, when Lomonosov made plans to establish M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University, Shuvalov persuaded the Empress and made the plan a reality. For this reason, Shuvalov is considered to be one of the founders of M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University along with Lomonosov.

He wrote many poems on this theme and received reward for it. One of the reasons why Lomonosov was recognized at court for his poetry and was later able to establish M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University was the presence of Empress Elizabeth's favorite, Ivan Shuvalov (1727-1797). Shuvalov was the only high-ranking official who could report directly to the Empress, and introduced Lomonosov's poems to her. Also, when Lomonosov made plans to establish M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University, Shuvalov persuaded the Empress and made the plan a reality. For this reason, Shuvalov is considered to be one of the founders of M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University along with Lomonosov.

After returning to Russia in 1741, Lomonosov returned to the Academy of Sciences, but from this time onwards he continued to fight with the Academy's upper echelons, led by I. Schumacher, for almost the rest of his life.

Although he continued to live in poverty, the following year, at the age of 30, he was finally appointed assistant at the Academy of Sciences and devoted himself to his studies. The Academy, run by a German, had not been able to produce a single Russian member of the Academy, even after 20 years since its establishment. In other words, Peter I's original intention of introducing excellent academic achievements and technology to Russia and nurturing scholars had not been realized. Growing up as the son of a fisherman who dealt with the harsh natural environment, Lomonosov had an impulsive personality and often clashed with the higher-ups. He was even placed under house arrest for about a year for verbally abusing an academician. Meanwhile, his wife Elisabeth, who had been left behind in Germany, came to her husband in Russia with their daughter. From then on, the couple lived together for the rest of their lives, with Lomonosov supporting him from behind the scenes as he devoted himself to his work.

Although he continued to live in poverty, the following year, at the age of 30, he was finally appointed assistant at the Academy of Sciences and devoted himself to his studies. The Academy, run by a German, had not been able to produce a single Russian member of the Academy, even after 20 years since its establishment. In other words, Peter I's original intention of introducing excellent academic achievements and technology to Russia and nurturing scholars had not been realized. Growing up as the son of a fisherman who dealt with the harsh natural environment, Lomonosov had an impulsive personality and often clashed with the higher-ups. He was even placed under house arrest for about a year for verbally abusing an academician. Meanwhile, his wife Elisabeth, who had been left behind in Germany, came to her husband in Russia with their daughter. From then on, the couple lived together for the rest of their lives, with Lomonosov supporting him from behind the scenes as he devoted himself to his work.

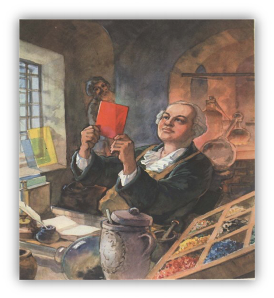

Lomonosov worked tirelessly to contribute to the development of Russian academia and to the development of human resources. His research fields were diverse, including chemistry, physics, astronomy, geology, geography, history, and literature, and he made extremely important contributions to both basic and applied research. Lomonosov said that his main specialty was chemistry. In 1745, at the age of 34, Lomonosov established Russia's first chemical laboratory.

After a difficult struggle, he won permission to set up a laboratory, which was said to be the best in Europe at the time, where he conducted various experiments for 10 years and trained young scientists.

After a difficult struggle, he won permission to set up a laboratory, which was said to be the best in Europe at the time, where he conducted various experiments for 10 years and trained young scientists.

At the Academy of Sciences, Lomonosov not only conducted academic research, but also analyzed minerals, worked on behalf of shipping and military agencies, and even produced fireworks for the imperial court and national festivals, at the command of the Tsar. Despite these busy days, he continued to achieve many research accomplishments.

At the chemical laboratory, Lomonosov lectured students and taught them experimental techniques.

Lomonosov was the first in the world to establish the "Law of Conservation of Mass" as a universal law of nature, deriving the law in 1756 through experiments on heating metals. Later, in 1774, the French physicist Lavoisier conducted precise quantitative experiments and proposed it as the "Law of Conservation of Mass," but Lomonosov's contribution to the "Law of Conservation of Mass" is hardly known in Japan. Lomonosov was also the first in the world to establish the field of physical chemistry.

Research into glass and ceramics holds a special meaning for Lomonosov. He conducted more than 4,000 experiments, creating colored glass in a variety of colors,

He also left behind numerous mosaics using this technique.

He also left behind numerous mosaics using this technique.

Lomonosov is also known as the "father of astrophysics." Born on the shores of the White Sea, he had been fascinated by the aurora since childhood, and he conducted experiments to elucidate the principles of the aurora.

He also worked with German physicist and member of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences G. Lichmann on lightning discharges, and together they developed a lightning generator. However, Lichmann was killed by lightning during an experiment. Lomonosov was deeply saddened by the death of his colleague and friend, and spent his life caring for his surviving family.

Lomonosov also made a great contribution to the field of astronomy. In 1761, while observing the transit of Venus across the Sun, he noticed that the surface of the Sun became undulating at the moment Venus left the Sun's face, and discovered that this was the refraction of light in Venus' atmosphere, meaning that Venus has an atmosphere. The transit of Venus across the Sun is an extremely rare phenomenon, and although astronomers from all over the world were observing it that year, Lomonosov was the only one to conclude that Venus had an atmosphere.

Lomonosov's achievements in the humanities must also be mentioned.

In addition to his poetry and his advocacy of new Russian poetic methods, he also wrote works in history and linguistics.

In addition to his poetry and his advocacy of new Russian poetic methods, he also wrote works in history and linguistics.

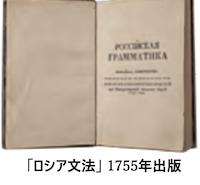

In 1755, Lomonosov published the results of six years of research into the Russian language in his "Russian Grammar," which remains an extremely important work in Russian linguistics.

Lomonosov's "Ancient History of Russia" was published in 1766. At the time, the Academy of Sciences, which was dominated by Germans, advocated a "Norman origin" for the founding of the Russian state, but Lomonosov was completely opposed to this, arguing that the origins of the Russian state lay with the Slavs in the Baltic region.

For the promotion of education

Lomonosov was devoted to nurturing Russian scholars. In one poem he wrote, "Russian soil will give birth to the Russian Plato and the agile Newton." To that end, Lomonosov wanted to create a university where anyone who wanted could study. As mentioned above, Lomonosov conveyed his idea for Russia's first university to Empress Elizabeth through his good friend Ivan Shuvalov. Then, on January 25, 1755, the Empress signed the decree to establish M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University, and that day became the anniversary of the founding of M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University. Today, January 25 is "Russian Students' Day."

In his plan to establish a university, Lomonosov proposed the establishment of three faculties: philosophy, law, and medicine. Anyone who wanted to study could study at the university, regardless of their social status, and even children of lower classes could enroll, except for serfs.[1] "The students who are respected at the university are the ones who have learned more than anyone else, regardless of who they are. It doesn't matter who they are," Lomonosov said. In addition, due to the need to first educate students to study at the university, a gymnasium[2] was also established at the same time as the university.

The initial faculty consisted of ten people, most of whom were invited from abroad, three of whom were Russian, two of whom were students of Lomonosov. Although Lomonosov himself never lectured at M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University, nor did he attend the opening ceremony, his students inherited the spirit of their master and scholars were nurtured in this temple of learning that was, in effect, Russia's first secular university.

In the field of education, Lomonosov also worked hard to reform the university and gymnasium attached to the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences. The gymnasium in St. Petersburg at that time was an old building with poor conditions. In winter, teachers wore furs and gave lectures while stretching in the classroom. However, the students were not provided with warm clothes and were not allowed to get up from their seats, so they shivered. Under these conditions, their health deteriorated, and they eventually developed scabies and scurvy, and were forced to repeat the year due to illness. At the age of 46, Lomonosov was appointed as an adviser to the St. Petersburg Academy's secretariat, and he worked hard to acquire a new school building to improve the situation, but by the time this was realized, Lomonosov had already passed away.

In addition, while university lectures in Europe at the time were generally given in Latin, Lomonosov gave the first public lecture on physics in Russian in 1746 (at the age of 34). This contributed to the dissemination of physics knowledge to the intellectual class and marked a breakthrough in university lectures being given in Russian.

[1] In fact, there were cases where landowners enrolled their serfs in schools in order to give them an education and allow them to do higher-level work.

[2] Secondary education institutions. Lomonosov said that having only universities and no secondary education institutions was "like an unplanted field."

After a relentless struggle

In addition to the academic achievements mentioned above, Lomonosov also made proposals on the population problem. At the time, Russia was a large country, but the population density was low and the child mortality rate was high. In 1761, he wrote a letter to Shuvalov, "On the Maintenance and Increase of the Russian Nation," which proposed ways to overcome this situation. In it, he suggested that in order to increase the birth rate, the people must be healthy, and for that reason, for example, the period of fasting in Russian Orthodoxy should be set in warm seasons rather than winter, that men and women of childbearing age should not be forced to become monks, and that the custom of the bride and groom meeting for the first time on their wedding day, which is decided entirely by the parents, should be abolished. However, these proposals were too radical for the times, and Shuvalov did not show them to anyone, and they were only made public a hundred years later.

Lomonosov's many achievements were met with opposition and obstruction whenever he tried to start something, but he fought through it and won one by one. Lomonosov always had many enemies because he was frank in expressing his opinions and fighting against injustice. This struggle continued until his later years, and he was always plagued by financial difficulties, but he managed to make a living by earning extra income from translation and poetry. In this environment, Lomonosov's position did not rise easily, but after being elected a member of the Royal Swedish Academy in 1760, he was given the title of procurator in 1763 at the age of 52 (two years before his death), and finally became financially stable. During the reign of Empress Elizabeth, his favorite Shuvalov supported Lomonosov's business ventures, but during the reign of Catherine II, Shuvalov also lost his power. In 1864 (at the age of 52), Lomonosov, who was surrounded by enemies, received the news that he had been elected a member of the Bologna Academy of Sciences and Arts, a prestigious academic institution in Europe.

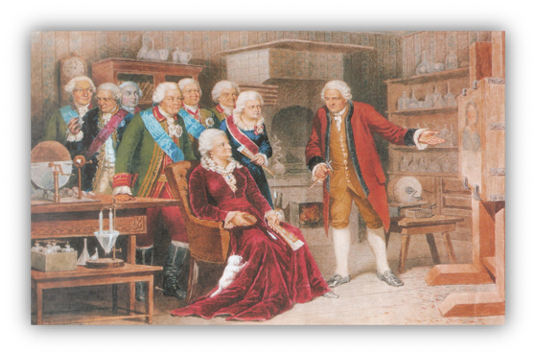

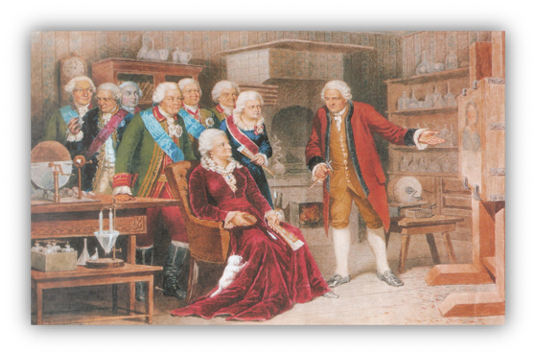

Shortly after Lomonosov's achievements were recognized by the Russian emperor, Catherine the Great visited him at his home, where Lomonosov explained his mosaics and inventions to the Empress.

Shortly after Lomonosov's achievements were recognized by the Russian emperor, Catherine the Great visited him at his home, where Lomonosov explained his mosaics and inventions to the Empress.

The following year, in 1765, at the age of 53, Lomonosov died of pneumonia at home. Born to a fisherman on the frontier, he overcame many hardships to build the foundations of Russian scholarship, and ended his eventful life. Lomonosov's many achievements were forgotten for about 100 years after his death, but were later rediscovered and are now remembered in history as the "father of Russian scholarship."

References:

Жажда познания. Век XVIII/ Н. Советов, А.

М. В. Ломоносов. Избранные произведения.

Юрий Нечипоренко. Помощник царям. вского университета, 2011.

by Evgeny Podkovitzin. Op. cit.Illustration